This year marks the 40th anniversary of John Carpenter’s Christine. To mark the occasion, the film enjoyed a theatrical rerelease in the United States last month and in the United Kingdom this week.

Situated in the middle of Carpenter’s phenomenal run that stretches from Assault on Precinct 13 to They Live, Christine is frequently overlooked in favor of movies like Halloween or The Thing. It says a lot about the quality and consistency of Carpenter’s output that movies like Christine and Prince of Darkness tend to be ignored because they are simply “very good” rather than genre-redefining masterpieces. Still, Christine is a movie that feels ripe for reappraisal.

Carpenter arrived on Christine by accident. His adaptation of Stephen King’s Firestarter was derailed by the commercial failure of The Thing, making King’s Christine a second choice. In hindsight, he concedes Christine “turned out better than it had any right to.” Discussing Bryan Fuller’s planned re-adaptation of King’s novel, Carpenter simply offered, “Well, good luck to him. It will probably be better.” (It remains to be seen if Fuller’s version will make it to screen, given the allegations of harassment against him.)

Still, Christine has developed something of a devoted cult following over the decades. Notably, it was a key influence on David Gordon Green’s Halloween Ends, to the point that Green asked Carpenter to let him know if the script was “too Christine.” Halloween Ends’ Corey Cunningham (Rohan Campbell) shares a surname with Christine’s Arnie Cunningham (Keith Gordon), and both characters find work in junkyards fixing up cars. Both young men also undergo similar transformations.

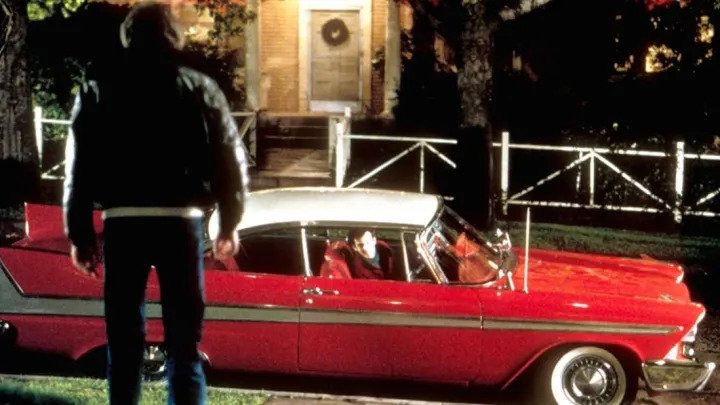

Stephen King’s Christine is obviously the story of a killer car, a concept that is ripe for mockery. To a certain extent, Carpenter just plays this straight. The movie’s opening sequence has the soundtrack play “Bad to the Bone” as the car rolls through the Detroit assembly line. Seemingly operating from pure malice, the car breaks the hand of one auto worker (Joe Unger) and murders another (Art Evans). Carpenter never explains why the car is evil. It just is.

However, like a lot of Kings’ novels, Christine is rich with subtext about masculine anxieties. Indeed, Carpenter and King make for a good pairing, sharing a lot of similar influences and interests. Jumping forward in time by two decades, the car finds its way into the possession of Arnie Cunningham. Arnie is a nerd and a loser. He’s bullied at school by Buddy (William Ostrander) and at home by his mother Regina (Christine Belford). Arnie is a young man stewing in resentment.

Much of that resentment is explicitly sexual in nature, even before the car gets involved. In his very first scene, he chats with his best friend Dennis Guilder (John Stockwell) about wanting to lose his virginity. He also complains about the game of Scrabble that he played with his mother the previous evening, which he lost because she disqualified his use of the word “fellatio.” He recalls, “She said obscenity’s not allowed in scrabble. I looked it up. It’s in the dictionary.”

Christine is not always subtle in communicating its theme of frustrated masculine anxieties. At one point, Regina sends her son to school with a packed lunch that includes a yogurt. Buddy steals the brown paper bag and penetrates it with his switchblade. The white goop splatters all over the floor of their shop class. There is a sense that something is simmering below the surface, that Arnie’s masculine and sexual anxieties are being sublimated.

They seem to be sublimated into the car. As the name implies, Christine itself is frequently gendered and sexualized. Even before he buys the car, Arnie refers to it as “her” and “she.” The previous owner, George Lebay (Roberts Blossom), recalls that Christine “had the smell of a brand new car. That’s just about the finest smell in the world, except maybe for pussy.” Later in the movie, Arnie opines that “there is nothing finer than being behind the wheel of your own car, except maybe for pussy.”

However, Christine is presented as an alternative to feminine sexuality. The car’s violence is often framed in explicitly sexual terms and often in masculine sexual terms. Christine is very forceful. It rams and crushes. It asphyxiates. The car squeezes itself down an impossibly narrow loading bay to cut Buddy’s friend Moochie (Malcolm Danare) “in half,” recalling a Family Guy joke. It later rams Buddy’s car repeatedly, smashing into a garage. That garage then explodes dramatically.

Arnie is fixated on sex, but from a place of insecurity. When he invites Leigh (Alexandra Paul) on a date to a drive-in, he feels impotent as Christine tries to choke her. He watches powerlessly as another patron performs the Heimlich maneuver on his date. Shot from a low angle, with rain falling as the pair thrust and grunt, ending with both collapsing in satisfaction, this is an explicitly sexual scene. Arnie is watching Leigh and another man. “Get your goddamn hands off her!” he screams.

However, Christine is not really interested in the relationship between Arnie and Leigh. Leigh is introduced as a potential love interest for both Arnie and Dennis, but then just drifts through the movie. The film is much more fascinated by the dynamic between its two male leads. In particular, the idea that the car itself comes between the relationship that these two young men share. “I know you’re jealous,” Arnie tells Dennis when his friend voices concern about the car.

Dennis is a fascinating contrast to Arnie. In many ways, Dennis is more conventionally masculine. He plays football, he drives a car, he is popular with the girls at school. If Arnie is a stereotypical nerd, then Dennis initially appears to be a stereotypical jock. However, as Christine unfolds, Dennis comes to embody a much more complicated and nuanced sort of masculinity. Indeed, it often seems like Arnie himself misunderstands what makes Dennis so much more popular and so much happier than he is.

Dennis is not hyper-aggressive. When he catches Buddy bullying Arnie, he doesn’t solve the situation by resorting to violence; he summons their teacher, Mr. Casey (David Spielberg), and reports Buddy’s switchblade. Dennis is portrayed as genuinely caring. He is constantly looking out for Arnie. There’s a compelling vulnerability to Stockwell’s performance, who plays the second half of the film as if Dennis is constantly on the verge of breaking into tears. Dennis understands his own feelings.

There’s a definite subtext to Arnie and Dennis’ relationship. When Arnie confesses he is drawn to the car because “for the first time in [his] life, [he] found something uglier than [him],” Dennis replies, “You’re not ugly, Arnie.” When Arnie rejects this, Dennis adds, “Queer, maybe, but not ugly.” On the page, this moment could be read as casually homophobic in the way that many movies of the era are. However, as played by Stockwell, it’s strangely tender. As he drives away, Dennis listens to Bonnie Raitt’s “Runaway”: “As I walk along I wonder what went wrong with our love, a love that was so strong.”

Arnie lacks Dennis’ comfort in his own skin. Befitting a movie released in the middle of Reagan’s first term, wealth plays into this. Arnie lives in the suburbs and is going to college. His mother dislikes that he is taking shop class, as if “it embarrasses her or something.” Class informs Arnie’s relationship with Darnell (Robert Prosky), who runs the auto shop. Darnell insists the shop is for “working stiffs gotta keep their cars running so they can put bread on the table,” not wealthy dilettantes slumming.

Over the course of Christine, Arnie transforms himself from a seemingly sweet and timid nerd into a complete monster. Christine predated Revenge of the Nerds by a whole year, but there was undoubtedly something stirring in the popular consciousness. Christine has aged remarkably well; the study of a young man who channels his own insecurities and frustrations about his inability to embody a stereotypical masculine ideal into something poisonous and monstrous.

That said, Christine hits on many of Carpenter’s recurring themes and fixations. After all, it directly followed The Thing, which is also about a set of unarticulated masculine anxieties. However, there are other points of overlap within Carpenter’s filmography. Christine feels like a strange companion piece to Halloween. Like King’s source novel, the bulk of Christine is even set in 1978, the same year as Halloween. Both are also stories about suburban repression.

In some ways, Christine is a gender-flipped take on Halloween. Carpenter has argued that Halloween is best understood as the story of Laurie Strode’s (Jamie Lee Curtis) sexual frustration. “The one girl who is the most sexually uptight just keeps stabbing this guy with a long knife,” he explained. “She’s the most sexually frustrated. She’s the one that’s killed him. Not because she’s a virgin but because all that sexually repressed energy starts coming out. She uses all those phallic symbols on the guy. She doesn’t have a boyfriend … and she finds someone — him.”

By this logic, Laurie seems to almost conjure Michael Myers (Nick Castle) back to Haddonfield. During their very first encounter, as she drops the key off at the old Myers house, she sings idly to herself, “I wish I had you all alone.” Myers steps obligingly into shot. In her conversations with her friends Lynda (P J Soles) and Annie (Nancy Loomis), it becomes clear that Laurie does have desires, even if she refuses to act on them. As Carpenter puts it, Laurie “is more like the killer, because she’s repressed.”

The Halloween series repeatedly uses “Mr. Sandman” as a music cue, as if Michael is Laurie’s dream manifested. The use of that song, much like the use of so much 1950s rock-and-roll in Christine, suggests the repression that informed that decade. In Christine, Arnie’s own repression seems to attract and empower the 1958 Plymouth Fury in the same way that Laurie’s repression seemed to draw Michael. All those unarticulated feelings have to go somewhere, and the results are horrific.

Of course, allowing for the opening scene of Halloween Resurrection, Laurie always vanquishes Michael. Arnie is not so lucky. At the climax of Christine, he stumbles out of the car and grasps Leigh. He gasps and collapses, a sequence just as sexual as the Heimlich maneuver earlier in the film. Ultimately, it’s revealed that Arnie has achieved penetration: a shard of glass sticks through his abdomen. Arnie has been impaled by Christine. Repression kills.